Marcellus Wiley

He came cross country to get an Ivy League education in case a future in football failed to pan out. As it turned out, Marcellus Wiley became the catalyst in an increasing trend of Ivy Leaguers in the NFL.

When Marcellus Wiley first arrived at Columbia University during the summer of 1992, the 6-foot-1, 185-pound running back from California was an unlikely candidate to leave Morningside Heights as one of the most influential football players in the Ivy League's storied history. But three inches, 95 pounds, a position change and four years of maturity later -- that is just what has happened.

A testament to Wiley's influence was the success of the 1996 Columbia team. That year the Lions jumped out to a 6-0 start for the first time in more than 40 years. That sixth win was a close one, a 13-10 victory at Yale, as Wiley ran wild -- blocking a field goal, sacking the Eli QB twice and picking up 35 rushing yards on seven carries. It was a performance for the ages, prompting Columbia Coach Ray Tellier to tell the press, "He did it all."

The Lions' run would come up short the next week in a heartbreaking 14-11 loss to Princeton, but they still ended that memorable season as one of the best teams in school history. Columbia's 8-2 mark earned a second-place Ivy League finish and the most wins for a Lion team since 1903, thanks in large part to Wiley's leadership as a captain and dominance on the field.

"Marcellus was a vocal and effective leader," recalls Tellier. "He was very mature."

Wiley may have shown maturity in the locker room that year, but he also matured into a dominating physical presence on the field. The 6-foot-4, 280-pound defensive end ended his Columbia career with a stellar senior campaign, earning first-team All-Ivy and third-team All-America honors.

But even with all the individual accolades, Wiley attributes Columbia's success in 1996 to the commitment and positive approach of the entire team. "That season was especially nice just because we had a great attitude and we had a great time playing and practicing. Guys really took it seriously that year and it showed on the field."

Wiley played a role in instilling a winning culture at Columbia football that season, but he played an even more influential role in raising the bar throughout the League. Wiley was a unique talent that helped bring the eyes of professional scouts back into Ivy League stadiums. During the 1996 season, one pro scout told a reporter, "I never expected to be here."

"It's an honor to be considered almost a modern-day pioneer of Ivy League football," said Wiley. "I'm just glad that my opportunity and my talent provided some light for other guys to get opportunities."

Wiley's opportunity almost didn't come at all. "They actually found me looking for someone else -- an offensive lineman, I think his name was [Brian] Larsen from Dartmouth. I played against him and did well, and he gave me the opportunity to impress the scouts." And impress the scouts he did. The rest is history.

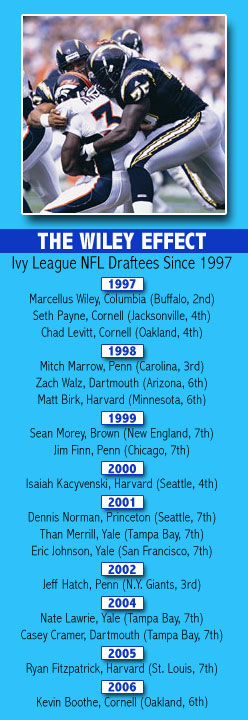

In the 10 years prior to Wiley being taken by the Buffalo Bills in the second round of the 1997 NFL Draft, only three other Ivy Leaguers were drafted by NFL teams. Only one of those players, Penn's Joe Valerio in 1991, was taken in the first seven rounds [today's NFL draft consists of seven rounds]. Since Wiley's selection, 16 Ivy Leaguers have been drafted, along with about a dozen more that have made NFL rosters as undrafted free agents. Wiley's profound influence on the revival of NFL interest in Ivy League talent is undeniable.

A 2000 NFL draft pick out of Penn, current New York Giant fullback Jim Finn, even goes as far as saying, "He's had the greatest impact of any Ivy player in the modern era."

Coming out of Los Angeles' Saint Monica High School, Wiley was heavily recruited by bigger, more traditional football schools such as UCLA and Cal. But he decided on Columbia for two specific reasons -- location and education.

He was eager to take on the challenge of adjusting to life in a new city, but the idea of an Ivy League education is what he found most appealing. "Just in case football didn't turn out to be anything beyond college it was a great safety net and just to say that not only I went to college but I went to an Ivy League school and graduated, I knew that sounded great on a resume, and it sounded great to my family."

So Wiley packed his bags and headed across the country to New York City where he enrolled at Columbia a sociology major with aspirations of becoming a teacher. Above all, Wiley was eager to use his time at Columbia as an opportunity to find himself. "I just really wanted to get a chance to learn about myself, learn about life, learn about what I wanted to do and what I wanted to springboard myself into after my four years ended."

And that is certainly what his college experience provided for him.

"I went from culture shock to understanding differences in others and differences in approaches. It's a very unique place where you can be a guy from inner-city Los Angeles who blasts rap music all day in your dorm room and your next door neighbor is from North Dakota playing opera, and you guys meet in the middle of the hall and just talk. Guys are from all different walks of life, different personalities; and you learn not to judge a book by its cover and take the time to learn what people have to offer and respect it no matter what it is."

This newfound appreciation for diversity gained during his time at Columbia is a valuable quality that Wiley has been able to carry over into his successful NFL career. "At Columbia guys were smart, guys were intelligent, and had various abilities and it wasn't about labeling them -- it was about understanding them. I think that carries over into the NFL because you have to learn how to pick up pointers and tips from other people despite who they may be. You have to learn to respect everybody and know that everybody has something to offer and a piece to the puzzle."

Columbia's life lessons have served the 10-year NFL veteran well. Wiley has put together a steady career, culminating in his 2001 Pro Bowl selection as a member of the San Diego Chargers. But even a trip to Honolulu hasn't caused Wiley to forget about his Ivy League experience.

"I think it's the best situation for any kid," he said. "When my kid gets of age and if they are all-world in sports and doing well in school I would not even consider sending them anywhere but an Ivy League school just because I think you can have the best of both worlds."

— Wesley Harris

|

|